How much do the views of scientists and experts count when it comes to securing public support for traffic restrictions? Laszlo Horvath and Deborah Mabbett find that the answer depends strongly on initial levels of opposition or support and look at the implications for policymakers seeking to shore up public support for such measures.

To what extent do the public listen to and trust scientists when forming views about policy? We would expect scientific views and evidence to carry considerable weight, especially around questions of public health. We used the contemporary case of clean air zones to examine to what extent the public responded to scientific cues when deciding whether to support or oppose traffic restrictions.

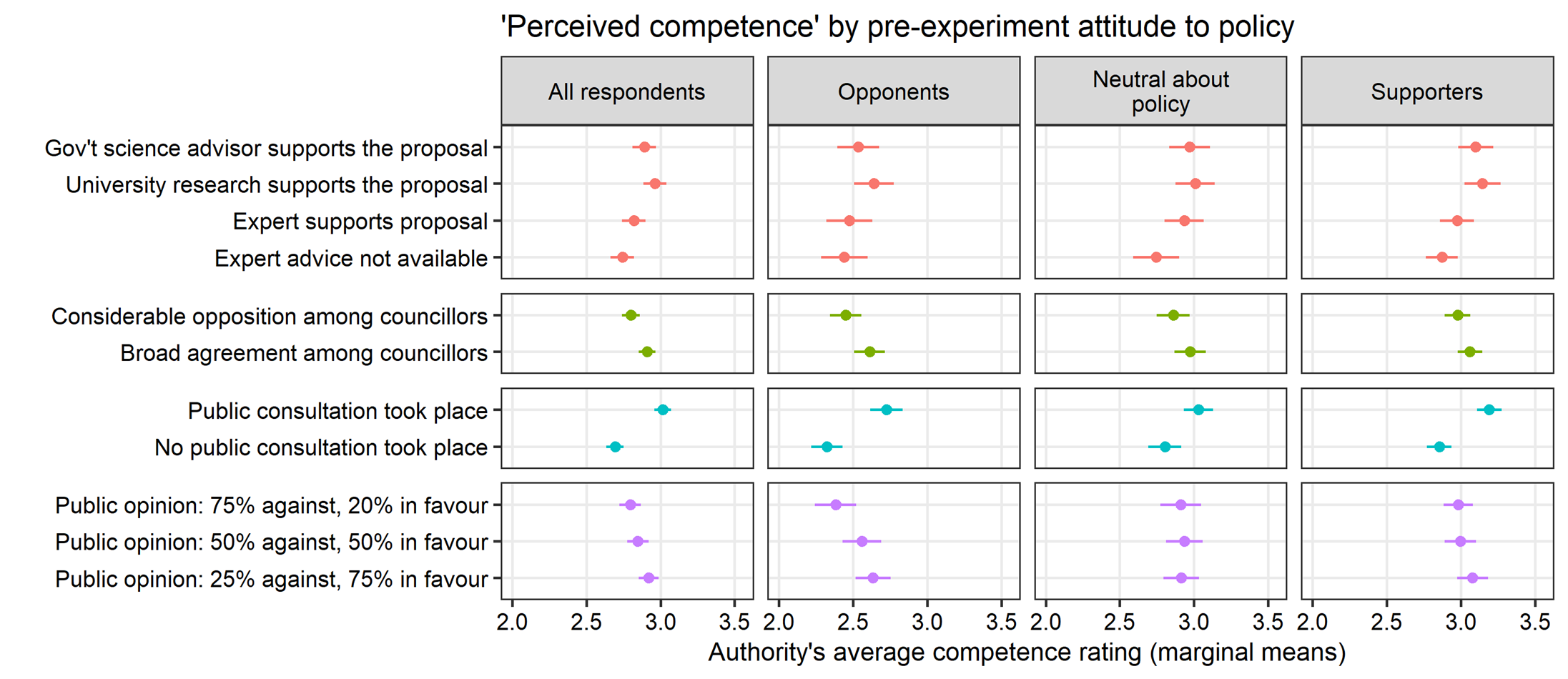

Our research used experiments to see if and when interventions by scientists were likely to sway people’s views about the case for policies: specifically, their assessment of whether the authority proposing the policy was competent and whether the policy process was fair and transparent. The experimental design also included other factors which might influence those views, such as whether a public consultation had been conducted and whether public opinion polls showed support for the measure.

Starting points matter

We found that expert support did improve respondents’ assessments of the quality of a policy, particularly of the perceived competence of the policy-making authority (compared with the base case of no expert advice being available). The strongest effect was attached to support coming from scientific research at a local or UK university. However, those whose prior view was negative towards clean air zones were not significantly swayed by expertise of any kind.

Furthermore, the positive effects of scientific support were not always the strongest compared with other policy features. Conducting a public consultation consistently outweighs the impact of science and expertise when it comes to perceptions of fairness and transparency. The existence of significant opposition to a policy proposal among councillors led respondents to downgrade their assessment of the competence of the policy-making authority. In addition, opponents of clean air zones gave considerable weight to information about public opinion about the issue.

Beware of vocal opposition

This suggests that people respond to “democratic” cues in their assessment of policies as well as expert cues. No doubt this is healthy in a free and open society, but the debate over the extension of ULEZ in London revealed three major issues with those cues. First, vocal opposition to a policy, often expressed in public consultations, can drown out widespread public support found in opinion polling. Second, vocal opponents may be basing their position on political objectives which are hidden from the public. Third, the drowning out of majority support is particularly likely if many people are hesitant to express a view, and this may be a particular risk with science-based policies where potential supporters are not confident in advancing scientific claims.

The public consultation on ULEZ attracted submissions that were clearly not representative of London’s population, including from outside the Greater London Authority area. Political scientists are used to the idea that those with the strongest vested interests shout loudest, and this can explain some of what we see in the public debate on ULEZ. Those most likely to have to pay the charge object, while those most affected by pollution may not take up the cudgels to defend their interests, as the benefits of the measure are distant, probabilistic and hard to put a monetary value on.

Political scientists are used to the idea that those with the strongest vested interests shout loudest

When Conservative-controlled councils and Conservative MPs lined up to oppose ULEZ, they made a great deal of the claim that it was “a tax on motorists”. They viewed the measure as a revenue-raising move, and furthermore one that would put funds at the disposal of the Labour Mayor of London Sadiq Khan. Given the financial squeeze on local government, these opponents are immensely suspicious of the temptation to use road pricing to raise revenue. ULEZ is hardly even a baby step towards road pricing since most vehicles are compliant but in the eyes of some Conservatives, it is the first step on a slippery slope and this is why they objected so fiercely.

From sitting on the fence to active support

While the majority of public consultation responses were opposed to ULEZ expansion, opinion polling commissioned by Transport for London (TfL) showed majority support, and other polls have also shown that those in favour outnumber those opposed. However, there are also high levels of “don’t know” (DK) responses. In the TfL poll, they had a striking social pattern. Only 16 per cent of men but 28 per cent of women were DKs; 18 per cent of ABC1s (higher status socio-economic groups) but 28 per cent of C2DEs (lower status). Those of white ethnicity were less likely to respond DK than members of other ethnic groups. These differences correlate to differences in ownership of vehicles and rates of driving. Given that women drive less than men, they may have declined to state a view due to not seeing ULEZ as “their” issue. Yet of course the detrimental effects of pollution on health are their concern, at least as much as men’s.

A recent study of low traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs) in London found that support for LTNs is higher among those who live in them (57 per cent compared with 47 per cent of those who don’t live in an LTN). This higher rate is entirely accounted for by lower DK responses, with opposition the same at 20 per cent. This implies that DK respondents are potential supporters of traffic restrictions, but they are wary of expressing advance support for a policy change with effects that they find uncertain. More confidence among the public in their scientific knowledge and understanding might help to convert DKs into active supporters, for example through “citizen science” projects which engage the public in measuring pollution and understanding its effects.

There is much concern and discussion in the scientific community about “anti-science” and the rejection of expert views, particularly on social media. But our research suggests that supporters of science-based policies should not be diverted by this noisy group, whose views often seem impervious to debate and persuasion. Instead, science advocates should consider why many people are reluctant to take a science-based view, and how their latent support might be mobilised.

This research has been funded by a British Academy “Science, Trust and Policymaking” grant, award number CST\220016.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit: Shutterstock